Research

Carbon emissions and stock prices in Europe – an investor’s perspective

Investors claim to incorporate environmental information in their investment decisions. Our analysis shows that investors in Europe fail to take account of the carbon emissions of companies and the risks resulting from high carbon-intensity.

Summary

Introduction and research question

Carbon emissions as driver for stock prices?

If one wants to understand what factors are influencing stock prices, the theoretical asset pricing framework sets out that stock prices are determined by investors considering possible future risks to the payoff of their investment. With climate change increasingly becoming a concern, potentially resulting in various risks for corporations, investors in the financial markets might see companies that exhibit low carbon efficiency or high carbon emissions as a risk to their investment portfolio. Some of these companies face political regulation-, which might become stricter in the future since policy makers, especially in Europe, are increasingly putting climate policy on the agenda[1]. The current European carbon pricing system, better known as the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), already includes most carbon-intensive companies. Furthermore, the carbon inefficiency of a company might signal that the company is an environmental laggard, staying behind competitors developing green technology. As a result, investors on average should be willing to pay lower prices for stocks of firms which are exposed to additional costs and policy risks due to their carbon inefficiency. In this study we extensively examine the empirical relationship between carbon emissions and stock returns in Europe from, predominantly, an investor’s perspective.

[1] European Commission. (2020). European Green Deal.

Investors face pressure to include information about sustainability in investment decisions

The question whether investors should consider corporate sustainability-related information in their investment strategies has been hotly debated for decades. In practice, every private or institutional investor has to decide for themselves whether and to what extent ethical and ecological considerations should affect his or her decision to invest their money. As a result of climate change and societal pressure on companies to incorporate Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), more and more investors are claiming they take account of sustainability-related information in their investment decisions. This can be shown by the growing number of institutional investors signing the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI). These signatories commit to mostly ESG-related investment principles. Currently they have about $103.4 trillion of assets under management, which have had an average annual growth rate of 23 percent since 2006[2]. This could be a sign of an ongoing shift in the financial industry towards acknowledging topics like global warming. Given that the planet is heating up faster than expected (Li et al. 2018, IPCC 2019), investors face a growing threat to their portfolios as a result of climate change-related risks like extreme weather events or political regulation (Krueger et al., 2020). Equity investors in particular should be particularly concerned since they would be the first to be affected by climate-related losses (Weyzig et al., 2014).

An increasing number of companies offer ESG reports to satisfy investors’ demand for company information beyond their financial performance. A growing number of institutional investors is starting to divest (sell owned stocks) from certain industries (Ritchie and Dowlatabadi 2015) as a consequence of the environmental performance of these industries. This makes sense as long as a small number of firms accounts for a large share of carbon emissions, which indeed is the case as shown by Figure 1. Given that almost 90 percent of all emissions are produced by only 10 percent of all companies, it should be relatively straightforward for investors to divest their assets to less emission-intensive companies. The incentive should be particularly strong, since the emission-intensity of, for instance, the most polluting 10 percent of companies is so much higher than for other companies.

[2] PRI brochure. (2019). Signatories Growth.

Figure 1: Share of corporate carbon emissions of companies sorted in deciles

Data and method

Emission data as basis for non-financial corporate evaluation

The number of corporations in Europe reporting their direct emissions (Scope 1) increased steadily over the last decade (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Companies reported on direct emission

To measure the carbon-emissions impact of stock listed companies on their stock prices, a large dataset for the years 2008-2019 was put together containing corporate emission data from large data providers like Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters and Carbon Disclosure Project. All datasets together contain over 900 companies reporting on their carbon emissions. Comparing the numbers of domestic stock listed companies in Europe[3] and firms who report on their direct carbon emissions in the dataset, the share of reporting companies increased from about 3 to 41 percent over the past 10 years. The size of the dataset illustrates that investors at least theoretically are able to consider the carbon impact of their investment decisions for many companies in Europe. Combined with corporate information about the stock prices, market value or revenue of companies for instance, it is possible to measure the influence of carbon emissions on stock prices in regressions controlling for several empirically known factors driving the prices of companies’ stocks.

[3] Worldbank. (2019). Listed domestic companies (total).

Research methods

We use different methods to investigate the effect of companies’ carbon emissions on their stock prices. All our models are based on state-of-the-art empirical research in asset pricing and therefore include widely accepted sets or explanatory variables (Fama and French 2018, Bolton and Kacperczy 2019). Because stock prices are deemed to not be suitable for this kind of empirical research, returns (change of stock prices from month to month) are used instead as dependent variable. As mentioned earlier, the relationship between risk and return is intuitively strongly positive. If an investment is seen as risky, i.e. the investor is prone to lose money, the returns as a reward for taking that risk are expected to be higher than for a less risky investment. At the same time, the price for a risky investment should be lower on average. Why should an investor pay a high price for a stock where the payoff is highly uncertain? High returns are seen as a sign of higher risk and investors are willing to pay lower prices on average for the stock in question. Building on these concepts, three empirical models are used to investigate the relationship between stock returns and carbon emissions.

First, we include the variables ‘carbon emissions’ and ‘emission efficiency’ in a panel regression alongside other factors affecting stock prices, such as the corporate book-to-market value and profitability. The influence of each variable on the stock price returns is measured by a regression coefficient. While the carbon emissions are of interest in matters of the corporate environmental impact, the emission efficiency factor both controls for the size of a company (since we do not look at the absolute emissions only but at emissions per revenue) and provides a measure for how carbon-intensive the revenue is which is generated by a specific company. The coefficient of these variables would represent a ‘Carbon Compensation Premium’, i.e. an additional stock price return compensating for the risks from high emissions or low carbon efficiency of a company. Additionally to account for ‘carbon emissions’ and ‘emission efficiency’, we include a dummy variable which signals whether a company in question is part of the EU ETS.

Second, we use the two-step Fama-MacBeth regression, which checks whether stock prices can be explained by a newly formed Carbon Risk Factor. This factor represents the difference in stock performance between carbon-efficient and carbon inefficient companies. If investors were to price companies differently based on their carbon efficiency, the carbon factor would appear as a significant driver for stock prices in the regression. Because this approach would prove that investors do see carbon inefficiency as a general risk, we call the effect ‘Carbon Risk Premium’.

Third, we check whether stocks are mispriced in matters of carbon efficiency, i.e. whether they exhibit a ‘Carbon Alpha’ as additional return. This can be shown by creating investment portfolios based on the carbon efficiency of companies. For instance, the 33% most carbon-efficient companies in the dataset are combined in one portfolio, the 34% medium-effective and the least carbon-effective 33% into two additional portfolios. If the portfolios offer additional returns (alpha), even when controlling for commonly known risk factors as market movements or firms’ size, investment or divestment in these portfolios might result in extra returns or averted losses for these portfolios, at no additional risk.

Study results

Empirical relation of Carbon emissions, EU ETS and stock prices

Following the Efficient-Market-Hypothesis, stock prices should at least reflect all past public information (Fama 1970). Therefore, information about climate change-related risks would be considered in investment decisions already. Indeed, recent empirical results indicate the existence of this carbon pricing effect in stock prices. According to recent literature, the information about climate risk in matters of corporate emissions seems to be priced all over the world including Europe (Bolton and Kacperczyk 2020).

However, this observation cannot be supported by the data used in the present study. The panel regression results as shown below show no significant impact of either carbon emissions (Scope 1-3) or carbon intensity as explanatory variables for stock prices.

Table 1: Panel regression results

These variables are not found to be statistically significant, which means that investors, on average, do not seem to require a Carbon Compensation Premium for the risk that corporate carbon emissions pose to their investments in European stocks. Furthermore, controlling for participation in the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) does not change the picture as one might expect. The EU ETS in Europe was introduced in 2005 as the first market-based, international trading system for emission certificates and is still the biggest of its kind worldwide. Companies working in energy-intensive sectors like energy production, steel production or oil refineries are obliged to buy certificates to be allowed to emit greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide (CO2) or nitrous oxide (N2O). Because the emission certificates represent an additional cost factor for companies, possibly bringing profits under pressure, investors would want to pay lower prices for stocks of these firms. However, this expectation cannot be validated by the data. Again, neither carbon efficiency nor carbon emissions of firms have a significant effect on stock prices. If we control for a company participating in the EU ETS using an interaction term, the outcomes are weakly significant. However, they point towards a negative relationship with returns and therefore into the unexpected direction. This result would suggest that carbon-intensive companies in the ETS seem to be considered to be less risky by investors (see box about limitations of the research). The finding that investors, on average, do not perceive corporate carbon emissions as a risk to their investment is strengthened by the results of the two-step Fama-MacBeth regression, because the Carbon Risk Factors explained above appear to be statistically insignificant as shown in the following table.

Table 2: Carbon Risk Factor

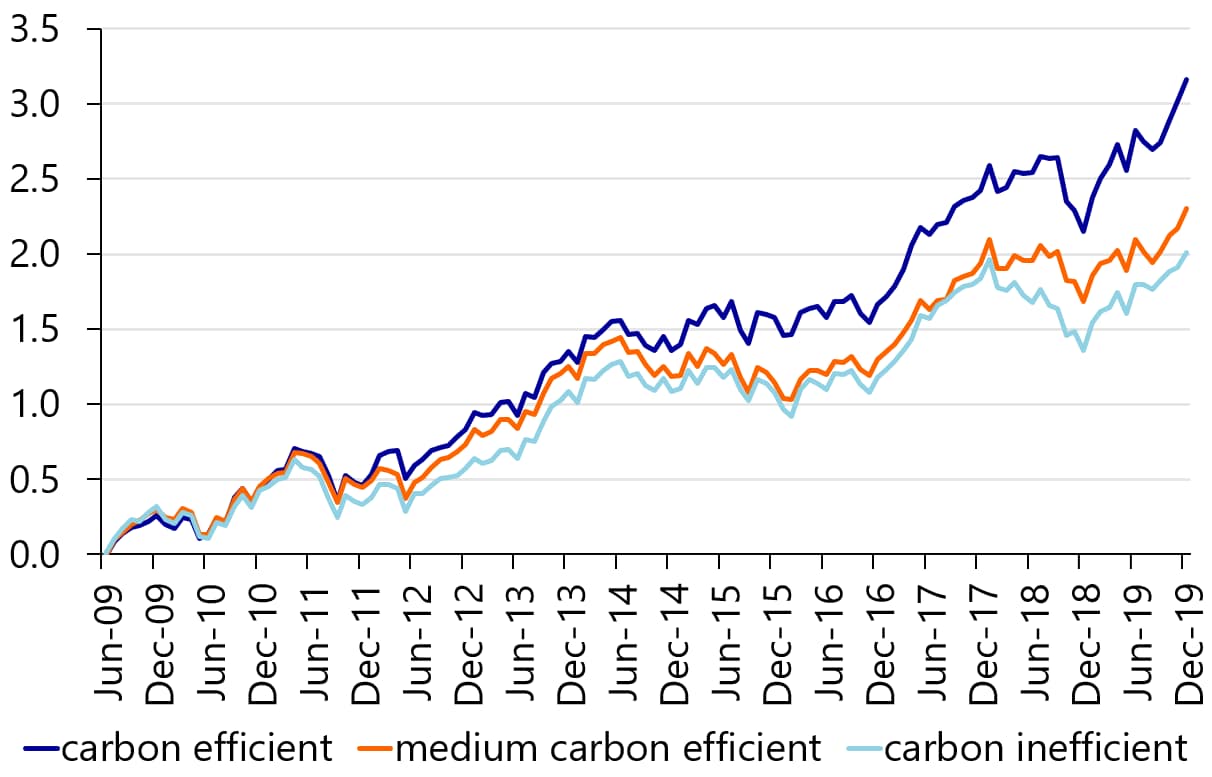

Even though we do not find a stock pricing effect on average in the last ten years in the regressions mentioned above, there are reasons to expect such an effect in the future. Comparison of the diverging cumulative results of three portfolios sorted on carbon efficiency, as shown in Figure 3, gives us an indication for potential future differences in stock evaluation. The first portfolio contains the companies most efficient in matters of carbon emissions, the second contains medium-efficient companies and the third comprises the least carbon-efficient firms (Figure 3). As we can see from the graph, the portfolio containing carbon-efficient stocks outperforms the other portfolios, especially after 2014.

Figure 3: Cumulative returns of investment portfolios sorted on carbon efficiency

Carbon efficiency: missing pricing or mispricing?

The results presented so far indicate that neither carbon emission nor carbon efficiency is priced into European stocks. This seems to be at odds with movements of institutional investors for carbon divestment and existing political measures like the EU ETS. On average, investors in European stocks apparently do not take carbon emission into consideration. The regression results are hence surprising, especially considering that recent research has found contradicting results (Bolton and Kacperczyk 2020).

Even though investors do not seem to price carbon efficiency on average, some do in fact include the environmental impact of companies in their pricing decisions. This results in different evaluations for the same stock, which might lead to mispricing. Indeed, the regression results show consistent mispricing in the form of additional returns which cannot be explained by known risk factors (called ’Carbon alpha’) of investment portfolios which vary regarding their carbon efficiency.

Limitations

Like any other research this study has its limitations which we want to briefly list. To begin with, there might be a selection bias as most of the companies included in this research voluntarily report their carbon emissions. Naturally companies not providing information on their emissions cannot be considered in this research. Furthermore, hidden heterogeneity might bias the results as important explanatory variables might be missing from our analysis. The outcomes regarding the ESG-dummy are somewhat difficult to interpret, because it can also be seen as an emission-intensive industry dummy. The relatively low R2 in the panel regressions indicates a general problem of asset pricing research that we face as well: the difficulty of calculating precise predictions of share price returns using linear models.

Discussion

The empirical results presented in the last section provide noteworthy insights into the relationship between carbon emissions, carbon efficiency and stock prices in the last decade and lead to three main conclusions.

These three findings could have different reasons and also severe economic as well as political implications.

The fact that carbon emissions are not reflected in stock prices is quite surprising, Considering trends like carbon divestment, ESG-reporting, alleged inclusion in stock pricing decisions, and increasing political action against climate change. It shows that investors have not yet fully internalized climate issues and related risks on company level. This is a missed opportunity: as the shareholders of a company, stock market investors have the possibility to influence decisions within a company and its corporate strategy. If they, however, do not seem to care about the carbon emissions or carbon efficiency of a company when buying stocks in the first place, companies face little pressure from the investors’ side to improve these aspects of their environmental performance. This implies that investors also seem rather unconcerned about the physical and political risks of climate change, although these risks are of increasing concern to academics, politicians and for regulatory bodies. The question arises why these investors do not seem to share these concerns. Investors that take account of carbon emissions in their investment strategies could use their influence as shareholders to foster corporate action regarding environmental impact. Political action at European level aims to provide the groundwork for this positive investor influence: the action plan for sustainable finance of 2018, for instance, aims to create more transparency with respect to ESG-reporting as well as regulations about labelling green financial products[4]. The EU Taxonomy, which is currently under development, will give further guidance regarding economic activities and sectors which contribute to sustainability, enabling capital markets to identify and respond to investment opportunities that contribute to environmental policy objectives.

Having regulatory systems in place should help to guide financial markets towards green investments. Sometimes, however, regulations are not entirely effective, as we can see from the result that investors do not take account of the fact that companies are part of the EU ETS in their pricing decisions. A possible reason for this is that the investors perceived the EU ETS to be non-binding and therefore inconsequential for the companies. A potential reason is that the cap, i.e. the maximum amount of allowances, has not been limited enough to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement, which means that too many allowances were in place. Moreover, during the last 10 years (Phase 2 and 3 of the EU ETS) many emission certificates were given out for free[5]. Therefore, it is not surprising that the current projections made by the European Environmental Agency forecast that the 80% emission reduction target until 2050 will not be reached[6]. Given these results, the effectiveness of the EU ETS so far could be questioned. This would also explain why financial markets do not seem to exert pressure on companies to improve carbon efficiency.

Reviewing Figure 3, however, gives us an additional perspective. There we can see that the carbon- efficient portfolio outperforms less efficient portfolios in terms of cumulative returns. It seems that investors require additional returns for the companies that are most carbon-efficient, which, according to the aforementioned risk-return logic, would mean that they perceive carbon-efficient companies to be more risky than carbon-inefficient ones. This, however, is highly counterintuitive. An alternative explanation could be the demand effect. As climate change has been gaining in importance in the last decade, investors might have started to hunt the same ‘green‘ stocks, driving up prices above the average market returns. Yet, this demand-effect theory is still at odds with the findings of the regressions explained above, revealing that there are many unsolved puzzles and research opportunities in this research area.

[4] European Commission. (2020). Renewed sustainable finance strategy and implementation of the action plan.

[5] European Commission. (2020). Free allocation.

[6] European Environmental Agency. (2019). Total greenhouse gas emission trends and projections in Europe.

Outlook

Pricing and regulation of carbon emissions has become a question of increasing importance for investors and policy makers in recent years. This is unlikely to change in the future considering the rapid developments in matters of climate change. In order to minimize transition risks and physical climate risks, investors are well-advised to consider the carbon footprint of their portfolios. With ongoing market trends towards sustainable investment, further regulation in financial and non-financial reporting and the better understanding of the economic impact of climate change, it is likely that a carbon stock pricing effect will appear in the years to come. The lack of data on carbon emissions can be addressed by political regulation as well as by shareholders demanding information. However, analysts, investors and data providers have to adapt their ways of evaluating investment opportunities. Actual mispricing in the market, which does not price carbon emissions of companies efficiently right now, provides opportunities for profitable investment strategies. The finding that financial markets do not perceive the EU ETS as important even for carbon- inefficient firms should make policy makers think and provide lessons for future regulatory design.

The transition to a lower carbon economy could clearly benefit from investors who take account of climate risks in their pricing decisions and from politicians setting the right incentives for green investment effectively and efficiently.

References

Bolton, Patrick, and Marcin T. Kacperczyk. ‘Do Investors Care about Carbon Risk?’ SSRN Electronic Journal. (February 6, 2020).

Bolton, Patrick, and Marcin T. Kacperczyk. 2019a. ‘Do Investors Care about Carbon Risk?’ SSRN Electronic Journal. (February 6, 2020).

Fama, Eugene F. (1970). ‘Efficient market hypothesis: A review of theory and empirical work’. Journal of Finance, 25(2), 28-30.

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 2018. ‘Choosing Factors’. Journal of Financial Economics 128(2): 234–52.

Li, C., Fang, Y., Caldeira, K., Zhang, X., Diffenbaugh, N. S., & Michalak, A. M. (2018). ‘Widespread persistent changes to temperature extremes occurred earlier than predicted’. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1-8.

P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.). (2019). 'Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems'. IPCC. In press.

Ritchie, Justin, and Hadi Dowlatabadi. 2015a. ‘Divest from the Carbon Bubble? Reviewing the Implications and Limitations of Fossil Fuel Divestment for Institutional Investors’. Review of Economics & Finance 5(2): 59–80.

———. 2015b. ‘Divest from the Carbon Bubble? Reviewing the Implications and Limitations of Fossil Fuel Divestment for Institutional Investors’. Review of Economics 5(2): 22.

Trinks, Arjan, Bert Scholtens, Machiel Mulder, and Lammertjan Dam. 2018. ‘Fossil Fuel Divestment and Portfolio Performance’. Ecological Economics 146: 740–48.

Weyzig, F., Kuepper, B., van Gelder, J. W., & van Tilburg, R. (2014). The Price of Doing Too Little Too Late: The impact of the carbon bubble on the EU financial system. Green European Foundation (Green New Deal Series, Volume 11).

Appendix

In the following the regression models are presented in more detail, setting out the regression equation and summary statistics of the variables used.

Equation 1: Main Panel Regression

The excess return of a company is displayed as the left-hand side variable. The control variables (1-9) can be found in Table A1. ![]() represents group fixed effect and

represents group fixed effect and ![]() the error term. ETS represents a dummy being 1 for companies in the EU ETS and 0 if not.

the error term. ETS represents a dummy being 1 for companies in the EU ETS and 0 if not.

Regression Model 2: 2-step Fama-MacBeth regression explanation

The first step which is performed as panel regression and includes an EMI (Efficient-Minus-Inefficient)-factor into the 5-factor-model (Fama and French 2018). In the following second step, the portfolio returns’ cross-section is regressed on the factor exposures calculated in step 1, for each time period providing a risk premia time series of coefficients for all factors. All factors represent the difference of returns (Table A2). For instance: Small-Minus-Big: The value weighted returns of small companies are subtracted from the value weighted returns of big companies.

Equation 2: Time Series Regressions

The excess return of different portfolios constructed on carbon efficiency is displayed as the left-hand side variable. The risk factors, control variables F are the same as shown in Table A2.

Co-authored by Paul Rösler during his internship at RaboResearch.