Research

ASEAN update: Recovering from Covid-19

We expect all ASEAN economies to grow this year, although at different speeds. The current high number of new Covid-19 cases underlines that the virus will continue to challenge economic recovery throughout 2021.

Summary

Virus continues to scourge the economy

New daily cases at an all-time high

We have left 2020 in the rear-view mirror and are looking forward to getting back to “normal”. Unfortunately, the coronavirus is still very much influencing our lives and the world economy. While scientists have learned quite a bit about the “original” virus, there remains much uncertainty about new virus mutations like the “South African” and “British” variant. The result is that 2021 will again be a year marked by the fight against the coronavirus.

Figure 1: New Covid-19 cases (daily)

Figure 2: Stringency of lockdowns (weekly)

This will also be the case for countries in South-East Asia. Although some ASEAN countries have been more successful in containing the virus (Figure 1), almost all have recently experienced record highs with regard to the number of new cases. Indonesia and Malaysia in particular have suffered a lot of new Covid-19 cases in the first months of 2021 and have had to increase lockdown measures (Figure 2). Although Vietnam and Thailand successfully contained the virus in 2020, even they decided to tighten their lockdown measures in December and January to prevent new varieties of the virus entering the country or spreading within their borders.

Vaccination status

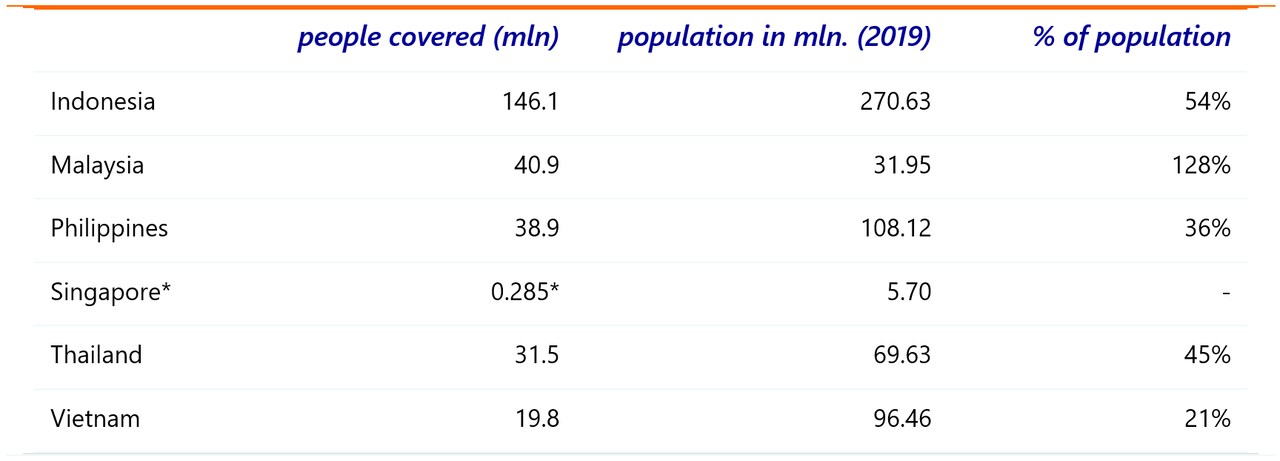

Local containment is one thing, but globalization has made virtually all economies interlinked, for example through supply chains, trade or tourism. This means that being able to fully open up in a safe and accepted way is vital for these economies to flourish. One of the means to achieve this is vaccination. There are large variations in the availability of different vaccines and in implementation strategies. Table 1 shows an overview of the contracts signed between ASEAN governments and pharmaceutical companies and how much of the population is currently covered by these contracts.

Although, at the time of writing, most ASEAN countries have not managed to secure sufficient doses to jab half of their population, they have been able to secure a reasonable amount of doses to, at least, start the vaccination process.

Table 1: Vaccine contracts in ASEAN countries

Table 1 gives an indication of the number of vaccines, but not of their quality or availability. The figures include contracts with different pharmaceutical suppliers. The supply of vaccines is not always readily available, although the countries covered in this report have all started or are starting a vaccination process in Q1 of 2021.

Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand started with the distribution of the Sinovac vaccine in Q1, which should be followed by the roll-out of AstraZeneca vaccines when these are supplied in Q2. Malaysia and Singapore started with the roll out of Pfizer vaccines in Q1. Vietnam aims to start distributing AstraZeneca vaccines in Q1. Nevertheless, all implementation is dependent on supply, which tends to be spread across 2021 and in many cases (except Singapore and Indonesia) does not appear sufficient to cover more than 50% of the population. We therefore do not expect herd immunity to be achieved for these countries (except Singapore) in 2021. By extension, this implies that new waves of the virus and subsequent lockdowns remain a realistic risk throughout this year.

Recovery at different speeds

Varying GDP growth

The containment of the virus is one of the major forces behind economic performance of individual countries. That was the case last year, and it remains important for the recovery paths this year as well. Table 2 gives an overview of our ASEAN GDP growth forecasts for 2021.

Vietnam is the best performer in the region, showing positive growth figures in 2020 which we expect to continue in 2021. Singapore has found the way up again: Covid-19 cases are low and demand for tech and medical products is surging, which (combined with an effective vaccine roll-out) makes for a relatively positive outlook. Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines are suffering from a high number of cases and are not expected to get out of the second dip before Q2. However, due to a low base in 2020 they are still able to grow significantly in 2021. An increase in tourism arrivals will spur growth from Q3 onwards if the global recovery persists and mobility increases due to implemented vaccine programs. Thailand seems to have overcome the second wave of infections recently but its economic recovery is slowing down. The lack of tourists, especially in the first half of the year, will drag economic recovery going forward, limiting Thailand’s economic growth in 2021.

As Table 2 shows, all countries are expected to find their way back into positive growth numbers in 2021. However, the pain of the pandemic will sting for years. The last column in Table 2 gives an indication of the impact of the corona virus on GDP. We have calculated the difference (in %) between our projected GDP at the end of 2021 and an estimate of GDP in In a no-Covid-19 scenario (i.e. if the pandemic had never happened).

Table 2: Projection GDP growth

Underlying dynamics

Although ASEAN countries are all dependent on external demand and economic growth in large economies like US, Europe and China, they differ in the composition of their economies. When we put differences in success of containing the virus aside, the different economic characteristics can explain the uneven recovery among ASEAN countries.

Figure 3 shows that Vietnam’s exports are already above pre-corona levels. Malaysia and the Philippines had a strong rebound from Q2 to Q3 2020. Singapore (-4% y/y) and Indonesia (-7% y/y) show a modest recovery and Thailand is lagging behind at -22% y/y.

The relative importance and composition of exports can provide an explanation in this regard. Vietnam was able to capitalize on the opportunity of diversifying supply chains away from China and an increase in the demand for goods as a result of lockdowns, keeping the economy afloat by an increase in exports. Malaysia benefited from increased demand for medical goods like personal protective equipment, which they both produce and export. Indonesia, as a rubber exporter, was also able to benefit from this.

Furthermore, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam and the Philippines are also experiencing increased demand in tech-related products (like integrated circuits, computers and telephones) due to increased working from home. On the other hand, Thailand and the Philippines might suffer from lower demand for office machine products as a result of more people working from home. Moreover, Thailand is an exporter of cars and vehicle parts, for which demand has fallen due to decreased mobility and companies postponing investments in capital goods like trucks and cars. Indonesia is a large commodity exporter, for example of coal, palm oil and gas. While demand in such products is lower in times of crisis, we are already seeing an increase in commodity prices in 2021 due to the global recovery, which enables these countries to catch up with regional peers.

Figure 3: Different speeds of recovery in exports

Figure 4: Tourism is another driver of the divergence in recovery

Another key differentiating factor is the dependency on tourism (Figure 4). The Philippines and Thailand are both very much dependent on the tourism industry, which contributes to more than 20% of their GDP. With regard to our expectations on the vaccine process, we expect that borders will at least be closed for the first half of 2021, remaining a drag on the economy. Service exports especially will stay on the back foot as long as global mobility is restricted. Singapore, Indonesia and Vietnam are less impacted by reduced tourism and less restrained on their path to recovery in this regard.

K-shape recovery and increased inequality

The large shock, positive or negative, in demand for certain products and services creates imbalances in growth not only between countries but also within countries. While certain sectors (like tech-manufacturing), are blooming, others (like tourism) are suffering. This is sometimes referred to as a K-shape recovery and this phenomenon also increases the risk of rising inequality. Something we already see happening in the US and China.

Facing the debt burden

Public debt is soaring

Governments have increased fiscal spending as a result of the pandemic. Additionally, economies shrank in 2020 (except for Vietnam), which decreased government revenues due to lower tax income (as a result of less economic activity and tax more deferrals). Larger expenses and smaller income lead to higher debts. Public debt increased significantly as can be seen in Figure 5.

All governments have announced additional spending in their budget for 2021 in order to battle the economic consequences of the pandemic. Figure 6 shows the fiscal deficit over the years, including this year. We observe very large increases in 2020 due to Covid-19 related expenditures. We do not expect these to come down to pre-pandemic levels in 2021. Governments have raised their maximum fiscal deficits for a limited number of years to provide budget flexibility to battle the economic consequences of the pandemic. For example, Indonesia introduced new rules which allows the government to exceed its 3% fiscal deficit limit for the coming 3 years.

Figure 5: Public debt soared in 2020

Figure 6: Fiscal deficits still high in 2021

Implications for future spending

Under normal circumstances, the increase in public debt would lead to higher risk aversion among investors, which in turn leads to higher yields and thus higher cost of borrowing for governments. However, during the corona crisis there have been other forces at play. As a reaction to the global outbreak of the corona virus and subsequent lockdowns, governments and central banks, especially in the US and EU, deployed enormous amounts of fiscal and monetary stimulus, which lowered yields in developed markets significantly. This has driven global investors towards riskier assets in search of higher yields, from which ASEAN countries were able to benefit. In Figure 7 we observe that bond yields decreased in all ASEAN countries in 2020, resulting in lower borrowing costs for governments. Unfortunately, these lower borrowing costs do not cancel out the extra costs of additional debt. Figure 8 shows our calculations for the debt repayments as % of total government revenue based on IMF estimates. All countries show an increase from 2019 to 2021, meaning that a larger part of government income needs to be spent on debt repayments. Money that has to be spent on debt repayments cannot be allocated towards other parts of the economy like infrastructure, innovation or the health sector. This can potentially result in lower future economic growth. Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines show the largest increase in relative debt repayment, essentially mortgaging their future.

Figure 7: Lower interest rates give some sort of relief

Figure 8: Debt repayments might hinder future fiscal stimulus

ASEAN currencies show strong recovery

Weak dollar paves the way for appreciation of ASEAN currencies

Figure 9 shows the performance of ASEAN currencies over the course of 2020. Four important events are marked in the chart and sketch the drivers of the behavior of ASEAN currencies versus the dollar: global investor sentiment is clearly in the driver’s seat. The first marked period is the start of the pandemic. Uncertainty led to a risk-off sentiment and saw investors retreating from the riskier EM markets into USD denominated assets. When uncertainty diminished due to the large monetary and fiscal stimulus packages, which were rolled out globally, we saw a gradual recovery through May and June. This was topped off by the second event when FED chairman Powell announced: “We’re not even thinking about thinking about raising rates" at the beginning of June last year. Having rates at near zero for a long time feeds into a ‘risk on’ sentiment, pushing global investors into risker assets in search of return, from which ASEAN currencies benefited. The third event was the US elections: the Biden victory was especially good news for Asian EMs as a Biden administration is expected to take a more positive foreign policy stands vis-à-vis South- East Asia. For Indonesia this coincided with other good news like the signing of RCEP and the renewed GDP agreement with the US, so we cannot say that this whole move is explained solely by the outcome of the US elections. The fourth event is the Georgia run-off on the January 5, 2021, where the Democrats won two additional seats in the senate. Expectations of larger fiscal stimulus packages in the US have weakened the dollar, and thus led to appreciating ASEAN currencies.

Figure 9: Currency performance and drivers 2020

Looking ahead, our base case is for ASEAN currencies to continue to perform, against the backdrop of a weaker USD. The additional stimulus package ambition set by the Biden administration, in combination with continued loose monetary policy by the FED and a global economic recovery on the back of vaccination programs should support risk-on sentiment and should strengthen ASEAN currencies during 2021.

Downside-risks scenario: looming inflation in US

However, recently we have seen a sharp rise in bond yields in the US on the ‘reflation trade’ and increasing inflation expectations in the US (as well as globally). Fundamentally we do not believe that sustained higher inflation in the future is a realistic scenario because the current slack in the labor market should prevent a domestic wage-price spiral taking hold. Nevertheless, the recent development has triggered us to sketch a downside-risk scenario for EM currencies, should the reflation trade and US bond yields continue to trend higher.

Irrespective of whether higher inflation actually materializes, the markets are testing the central banks’ willingness to act, or to comfort them. So the main question is: what are the central banks (FED in particular) going to do? If they react with strong verbal intervention and additional monetary policy measures, the market will probably shift back to risk-on mode, which would be beneficial to EM currencies. However, in a scenario (not our base case) in which the FED does not act or even tightens monetary policy, we could see more capital flowing back to the US, pushing up US yields and the dollar, depreciating most of the EM currencies accordingly. This would hurt many EMs, but probably commodity importers more than commodity exporters. Large depreciations in EM currencies could force central banks in EMs to hike rates in some cases. This would undoubtedly hurt the economies, which are just crawling out of recession.

Outlook for individual currencies

Besides the risk sentiment of investors, fundamental factors do play a role in pricing individual currencies. Zooming in on specific currencies we first turn to Indonesia. President Joko Widodo is doubling down on the reform agenda. Last October the administration introduced landmark labor reforms, increasing attractiveness of Indonesia as an investment destination. In January they released a draft presidential decree in which they further limit the number of sectors that are restricted to foreign investments. In combination with the signing of RCEP and the renewed GDP agreement with the US, we can expect the Rupiah (IDR) to appreciate in the long term. However, the slow economic recovery and high number of Covid-19 cases might trigger additional fiscal and monetary stimulus by the government and Bank Indonesia, which limits the short-term upward potential for the Rupiah.

In Thailand, the BoT left the policy rate unanimously at 0.5% but retains an accommodative stance. Recovering exports and increased demand for Thai export goods on the back of a global economic recovery should improve the current account in the second half of the year. In addition, borders will open to tourists, both strengthening the bath (BTH). Downside risks are related to social unrest and its negative impact on foreign investment and tourism once borders open.

The Philippine peso (PHP) appreciated in the last months of 2020. One of the reasons was an increased inflow of remittances sent by the Philippine diaspora to support their families amidst natural hazards (typhoons) and weak economic recovery. The economic recovery in the Philippines is disappointing and the fiscal and monetary stimulus packages relatively modest. However, inflation has been rising recently, restricting the central bank (BSP) to cut rates. The high demand for export products in combination with additional US stimulus that will probably lead to extra remittances to support family overseas, should both strengthen PHP in the short term. Over the medium to long term, PHP will benefit from government reforms in the form of the CREATE bill which will attract foreign investments from export-oriented companies.

The Malaysian economy contracted in Q4 after a strong rebound in Q3 and is expected to slide further in Q1 due to increased lockdown measures. The new surge of the pandemic has led the King to proclaim a national emergency until the August 1, suspending parliament and kicking the can with regard to political uncertainty caused by PM Yassin’s slim coalition majority. In the short term, the low inflation environment paves the way for additional monetary policy action to stimulate the economic recovery, limiting the extent to which the Malaysian Ringgit (MYR) can appreciate. On the flipside, global demand for medical and tech equipment and supply-chain diversification should continue to support MYR in the medium/long run.

In Singapore (SGD) the MAS set a zero slope on the nominal effective exchange rate policy band in October, as a reaction to the economic contraction and low inflation. This limits appreciation/depreciation against the basket of currencies and USD, which results in a relatively stable SGD in the short term. On the longer term, the revival of global trade dictates the demand for SGD. Singapore has a very open economy and the demand for SGD depends strongly on the recovery of global trade and how any lasting effects of the pandemic manifest themselves.

Table 3: FX Forecast